The struggle for online identity has been heating up lately. Facebook, LinkedIn, Google, MySpace, and a slew of startups are vying to be the primary keepers of your online identity: your personal info, your communications, and (most importantly) your list of friends. Erick Schonfeld at TechCrunch recently observed, “In the last ten days, Facebook, Google, and MySpace have all announced ways to let people access their data (including friends lists) from other sites, except that what they are really trying to do is erect new walled gardens by positioning themselves as the primary repository of that personal and social data.”

How will it all play out, and what is the best possible outcome?

In this longer than usual post, I want to show important parallels in today’s battle for online identity and the battle for online content over a decade ago. Furthermore, I’ll argue that online identity needs to follow a similar path. In short, the content battle was won by the internet largely because it was organized by a nonprofit agency instead of a for-profit company. Online identity is now in need of such an agency.

How the Internet won the battle for online content

An TV advertisement for Ford used to end with “Go to AOL Keyword: Ford”. AOL wanted their keywords to be THE gold standard addresses for content online. When someone thought “I wonder what Ford is up to?”, AOL hoped people would launch their software and type the “ford” keyword. To the extent that Ford Motor Company believed this, AOL could charge a lot of money for that 4-letter keyword.

AOL wasn’t the only one in this game. Some of you might remember other networks like GEnie, CompuServe, Prodigy, and many others. All of them hoped to be THE place where people would look for content.

However, all of those content networks were blown away by the internet. Few people today are aware there was ever an alternative. But why did it win? The internet had no advertising budget. It didn’t negotiate exclusive deals with MTV or the NYSE. And it had a tongue-twisting syntax: TV and radio announcers everywhere struggled to enunciate “h – t – t – p – colon – forwardslash – forwardslash – double-u – double-u – double-u”.

But the internet also had great advantages. Most notably, no one owned it. As a small company, you didn’t have to negotiate a deal with the internet to publish your content there. As a big company, you didn’t worry about the internet being purchased by a competitor. You also didn’t need the internet’s permission to download all it’s content for analysis. It’s no accident that Google didn’t launch first on AOL! So companies flocked to the internet: big and small, old and new, useful and ridiculous. The “Dot Com” suffix of the internet’s naming scheme became the became the label of the internet’s victory as THE online network.

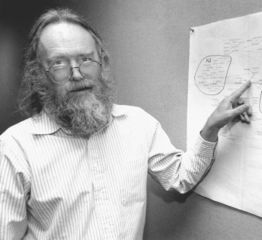

To say that “no one owned it” is not to say the internet was total chaos, devoid of any oversight. Someone had to connect “www.ford.com” to Ford’s servers. In fact, all those dot-com, dot-net, dot-org, and dot-edu addresses were managed by the United States Department of Defense. And DOD merely delegated internet addresses to one smart and funky-looking guy at UCLA, Jon Postel. When he died tragically in 1998, oversight of internet naming was transferred to a newly created non-governmental and non-profit agency called the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). Every time your browser loads a page you are using ICANN.

This system has worked so damn well that we all now take it for granted. There was never a fear of Postel or ICANN turning evil. There was no fear that they would start injecting ads at the top of your pages. There was no fear that they would sell your traffic data to your competitors. There was no fear that they would force you to buy proprietary server software. There was no fear that Jon Postel would call you one day and say “Sorry Ford, I’ve decided not to renew the contract for your domain name this year.”

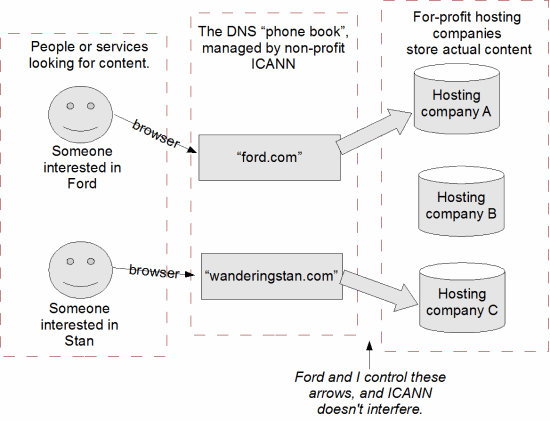

How does internet naming work?

The internet’s naming system is, in essence, a big phonebook full of names and servers. This phonebook is called DNS. So when you type “www.wanderingstan.com” into your browser, this name gets looked up in the DNS phonebook. The listing for “wanderingstan.com” is listed as “70.85.249.98”. That’s a server owned by my hosting company which I rent for $14 a month. But here’s an important bit: If my hosting company starts to suck, I can always go change my entry in that book and have it point somewhere else. And when I do this, I don’t have to tell everyone a different address. I own “wanderingstan.com” in perpetuity, and will always have it point to the server of MY choice.

(On a related tangent: For end users, search engines are beginning to usurp DNS as the primary addresses.)

What this has to do with Online Identity

Just as AOL, Prodigy, CompuServe and others battled to control online content, a war is brewing right now over online identity. Every company wants to be THE gold standard address for your identity. When someone thinks “I wonder what Stan is up to?”, Facebook hopes that people go to my Facebook page. MySpace hopes people will go to my MySpace page. Same for LinkedIn, Twitter, Google, Flickr and tons of others. Companies like SocialThing, FriendFeed, and Plaxo Pulse take the problem up one level and try to be THE gold standard by aggregating all the other would-be standards. But all of these “solutions” just shift the problem. I don’t want my online identity tied to Facebook or Plaxo any more than Ford wanted their online content tied to AOL or GEnie.

Ford can now tell people to go to “WWW.ford.com” instead of “AOL Keyword: ford”. What a huge difference there is between WWW and AOL! WWW is not going to get bought by Time-Warner. WWW is not going to set rules about what can or cannot be put on Ford’s site. WWW is not going to show advertisements against Ford’s content. WWW is not going to prohibit Ford from sharing data with 3rd parties. WWW is not going butt into the conversation between Ford and it’s customers.

The problem for you and me today is that we have no place to run to. There is no WWW for our online identity. There is only “facebook.com/id=252800001” and “myspace.com/wanderingstan” and dozens of others. Unlike for Ford, there is no ICANN or Jon Postel for our identities. There is no phone book we can get into without someone trying to monetize it. There is no social network that won’t butt into our conversations. Who can we trust to give us a lasting home for our identity?

Proposed Solutions

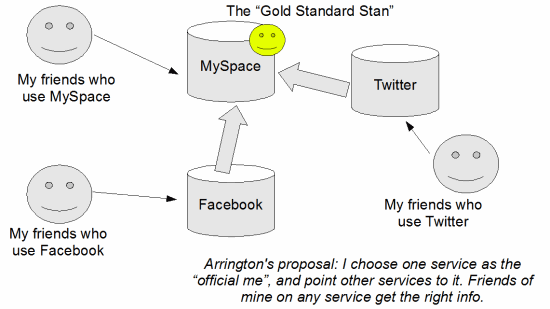

Michael Arrington recently described his ideal solution. He writes, “Ultimately I hope that I can keep my identity…at any service provider that I trust…and just tell sites like Facebook and everyone else where to grab it.” His proposal would look like this:

The problem is that I have no permanent address, just a lot of forwarding addresses. It puts the onus on me to provide my forwarding address to every service out there. This is impractical given the number of services that exist. Furthermore, it thwarts innovation by tilting the favor towards the established networks. Why would I risk using a newly launched service if I wasn’t sure all of my friends had left “forwarding addresses” there?

Those of you geeky enough to know about OpenID may be thinking that it is the solution we’re looking for. But the same problem arises in a different form: Your OpenID identity must always be tied to an internet domain. So of course, companies are now scrambling to have their domain be THE place to have your OpenID. AOL was the first big company to make all of their user accounts into OpenID accounts. They lost the war for naming online content, but now want a stake in naming all online identities. So now I can now login to any OpenID site as “http://openid.aol.com/wanderingstan”. Why do I want this? Why would I stand to have an “aol.com” as part of my online address, my identity? Once again, I don’t want my identity in the hands of AOL.

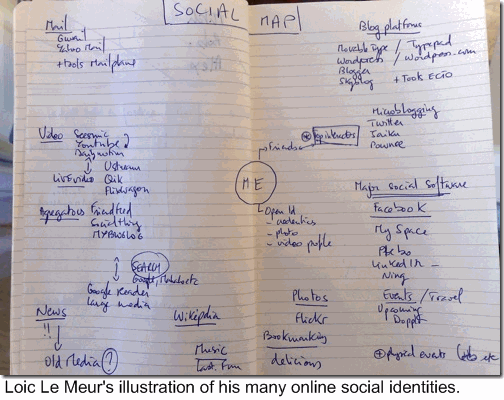

If you’re a true nerd reading this, you probably are saying “But Stan, you DO have a personal identity: it’s your domain at wanderingstan.com!” The thought here is: we can use the current DNS system and map identities onto it. This is was Loic Le Meur asked for in his widely cited post My social map is totally decentralized but I want it back on my blog. This is also a motivation for “.name” domains, like “stan.james.name”. This approach has the right idea, but fails to account for how identities are fundamentally different from a web site or company. For one thing, people won’t pay to register a domain for their identity, especially when it doesn’t get them anything. This is a topic unto itself, but we need a way where people can create and use identities (and multiple identities) for free, without being overrun by spammers.

Where do we go from here?

There are several ways that this could work, and the nerd in me is tempted to start explaining how OAuth, OpenID, P2P, and other acronyms could be combined to make this work. But I’m not here to sell a specific solution, just the idea that (a) we need a permanent home for our online identity(s), and (b) this home cannot and should not be tied to a organization that must try to monetize them. But I believe that we need some neutral ground for our identities, just as ICANN did for internet content.

Like the internet itself, maybe the solution is as simple as a phone book of pointers. So maybe “wanderingstan” points to Facebook today, and next year I’ll switch to MySpace. The important thing is that my change doesn’t mean a new address, re-creating my friend list, and typing in my favorite bands again. Maybe the phone book stores some actual content, like my avatar or friend list.

Sure, there are a lot of challenges to this approach. Personal Identity data is a lot trickier than Ford’s homepage. Privacy, for one thing. Ford wants “www.ford.com” to be viewable by anyone. Not everyone feels that way about their profile. (Although most people feel comfortable with part of their online identity being public, e.g. when reviewing a restaurant.) There is also the problem of allocating identifiers (what if someone else gets ‘wanderingstan’ first?), and dealing with squatters. However, these are all manageable problems.

Some might object that identities are more expensive to manage than simple domain names, and thus companies deserve to own our identities in exchange for the costs involved. Bullshit. The amount of data we’re talking about is pitiful. The costs of storage, bandwidth, and processing continue their march towards free.

Twenty years ago it was sensible to ask, “In the future, will more people read the news on AOL, Prodigy, or the internet?” That’s a fair question, but we now know that “reading the news” is only one of the zillion things that you can do with online content!! eBay, search engines, blogs, photo sharing, Wikipedia, social networks, and more every day. We would not have all these wonderful things if AOL had won the battle for online content. Even if they had a developer platform.

Today the sensible question is, “In the future, will everyone login to sites using their Facebook, MySpace, or Google login?” Twenty years from now, I’m sure this will seem as silly and short-sighted as the first question. As if “logging in” was the only thing you can do once you settle the identity issue! I wrote my thesis about one such application, and am frustrated that its full potential cannot be realized until identity is allowed out of the current data silos. I’m sure there are hundreds of applications that others have thought of but aren’t possible.

I’m not sure how it will happen, but I hope you’ll agree that we need a Jon Postel an ICANN today for our identities. The first step is to recognize this corner that we’ve been backed into. Perhaps the Facebooks and MySpaces and Googles of the world will cooperate to make this non-partisan agency. Perhaps, like with Postel and the DOD, it will emerge from a government agency. Perhaps it will grow out of non-profits, as did Craigslist or Wikipedia.

Or, maybe I’m full of shit and overlooking some obvious reason why this won’t work. Maybe the internet managed only because was able to organize itself before there were millions and billions of dollars at stake. Maybe Google, Facebook, MySpace and others will fight it out for years to come.

In any case getting tired of uploading my avatar to a new service each day, answering all those friend requests, and dreaming of all the amazing services that can be built once this war is over.