“The World-Wide Web was developed to be a pool of human knowledge, and human culture…”[1]

And so goes the story: a network designed to facilitate military communications in a nuclear war, a system of pages designed for scholars to link to each others work. Things don’t always turn out like they were planned, do they?

Okay, it was obvious years ago that the Web would not be an ivory tower of knowledge and culture, but nevertheless we just passed a landmark moment: Last year Facebook officially overtook Google as the most visited site on the internet.[2]

Facebook reports that their users now spend over 700 billion minutes per month on Facebook. It’s incredible that so many people think its worthwhile to spend so much time looking at this particular arrangement of pixels. They are not looking up facts, not soaking in culture.

This line of thinking always reminds me of an provocative idea from the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. Over a hundred years ago he said, paraphrasing, that the certainty of a belief is inversely proportional to the existential importance of that belief. [3] What does this mean in practice?

Consider two facts:

- Paris is the capital of France.

- Your friends care about you.

Both are true, right? But there’s a difference. In the case of Paris, you can be very certain. Thousands of books will confirm the fact, as will most any passing stranger. You can even go to Paris and inspect various government buildings. But is this fact important to you—you the existing, feeling, needing, mortal creature? Unless you live in France, not so much. On the other hand, your friends care about you. But how can you be certain? This isn’t written in books you can’t look it up in Google or Wikipedia. There is no place you can go and inspect to confirm their feelings for you.[4]

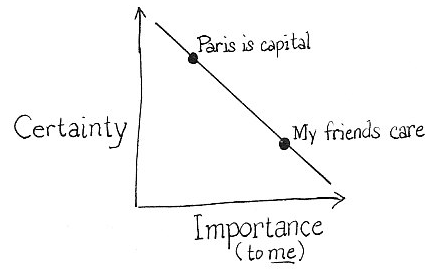

Kierkegaard’s books didn’t have graphs, but if they did, our two facts would show up like this:  You could add some other points to the line as well. Kierkegaard would put mathematics to the extreme left: facts infinitely certain, and infinitely irrelevant to your existence. And he would put your eternal destiny to the extreme right: a fact infinitely uncertain, yet of infinite concern to you.

You could add some other points to the line as well. Kierkegaard would put mathematics to the extreme left: facts infinitely certain, and infinitely irrelevant to your existence. And he would put your eternal destiny to the extreme right: a fact infinitely uncertain, yet of infinite concern to you.

This is the point where he continued on talking about faith, but let’s get back to our original, geek-ier, subject.

Those objective, Paris-ish, left-side facts can be confirmed with Wikipedia or Google. But where you can find the subjective, Friend-ish, right-side facts? You guessed it: Facebook. Of course it doesn’t give you hard evidence. There are no citations or PageRanks to rely on. But all those “likes”, “pokes”, “friends”, “updates”, “tags” and the rest add up to a general picture of caring, support, involvement. People are sharing with you, interacting with you. On college campuses, friends will ask if your new relationship is “Facebook Official” [5] That is, have you updated your profile to show you are in the relationship?

It’s all our attempt to bring a little certainty to things that matter deeply.[6] And it’s nothing new. In the pre-Facebook days we had to rely on other sources. Letters. Phone calls. Talks over coffee. An embrace. None of these were perfect indicators, of course. People misrepresent themselves all the time. And we all have “friends” there who are nothing of the sort.[7] The thing about Facebook, and the key to its success, is that it dramatically lowers the cost of getting a tidbit of that information. Just as Google and Wikipedia are easier than a trip to the library, a visit Facebook is “easier” than those letters, calls, or coffee dates.

Who could have predicted that this nuclear-proof system designed for furthering human knowledge and culture would one day be dominated by a program of “likes”, “pokes”, “friends”, “updates”, and amateur photos? It seems that this, after all, more closely approximated what we wanted.

[1] Wikipedia: World Wide Web

[2] Techcrunch: Facebook Overtakes Google To Become Most Visited Website In 2010. Facebook: Facebook Stats.

[3] Wanderingstan: The rise of subjectivity on the web. For example, “Kiekegaard thinks that to whatever extend something can be known through intercourse with the world-historical (i.e. objectively), the potential response elicited from an individual will necessarily be proportionately less passionate, resulting in less inwardness and less “truth.”” Michael P. Levine

[4] At least, not yet. For example see this study: The neural basis of romantic love (pdf)

[5] Urban Dictionary: Facebook Official

[6] Kierkegaard’s main point, in fact, was that Christian apologetics was a futile attempt to bring faith –and your eternal destiny– further to the left.

[7] Wanderingstan: Facebook acquaintances the new TV stars