[This is a long essay-ish post, reading time: about 7 minutes.]

You could say I’m writing this in response to an email I received in the Fall of 1997. No, I don’t have a backlog of thirteen years in my inbox. (Tough if you’ve contacted me lately you might disagree!) But it’s no exaggeration to say the email changed the way I look at life.

At the time I was working as a game designer for a small startup in Boulder, Colorado. My previous game had been a minor hit; Ultracorps was the first multiplayer game you could play entirely within a web browser. Microsoft had bought it a few months before, and there was pressure to make a game we could sell to AOL.

So far, things were looking good. Our new game Evernight, shifted from sci-fi to fantasy, and already had nearly a thousand beta testers playing. The game was turn-based, similar to the board game Risk, or Axis and Allies. During the day you could inspect your armies, manage your factories, and exchange diplomatic emails with other players. By midnight you had to submit orders to your forces, and then for an hour the game would be closed while armies moved about and fought their battles. The next day you would log in to see the results and start the cycle over again.

I and team members play-testing Evernight on paper before computer coding began, a few months before the email.

The finished game in an ancient web browser.

We knew the Evernight was good. It had been play-tested extensively in the conference room before we even began coding. (Those were some hard days at the office!) And now that it was live on our website, we could see how much people were playing it by looking at the server logs.

One player soon pulled ahead in the game rankings, conquering foes left and right, making all the right alliances, and pitting his enemies against each other. He was spending huge chunks of each day in the game, sometimes over six hours at a stretch. He began sending us report bugs and ideas for improving the game, and thus began our correspondence.

But the email on this day was different. He wrote, “My boss says that I’m playing the game too much at work, and says I have to choose between my job and the game.” Ah-ha! So that’s how he had so much time to play—he’d been playing at work.

“Well it wasn’t hard,” he continued. “I choose the game.”

Wait. A. Minute. I was just a kid having some fun, right? For most of college I’d been a wide-eyed idealist, thinking I’d live some monkish existence while saving the world. And here instead a guy was quitting his job so he could spent more time playing with my creation. This I had not foreseen.

The question was not simply about addiction, not only about computers and pixels on screens. It was about how he was choosing to spend his life, and how I was choosing to spend mine.

The core issue here is our value system. What do you find important, and why? Maybe you spend six hours a day playing games too. Maybe you don’t. In either case, why? For that matter, why did you chose to read this post? As a first pass at understanding that system in us that decides, lets consider two far-flung examples.

—

One hundred and sixty years before that email, another man was making another big decision. Charles Darwin, still twenty years away from publishing his famous theory of evolution, was thinking of asking one Emma Wedgewood to be his wife.

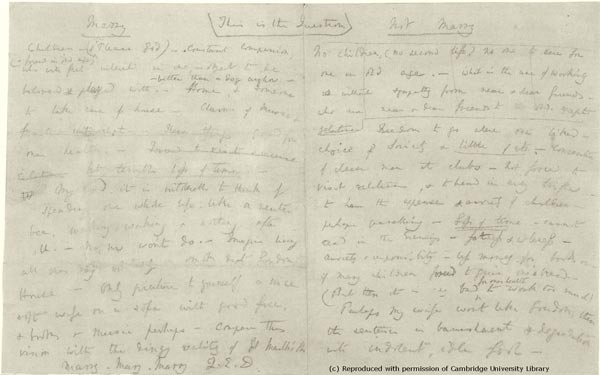

He did something that you probably have also done before some big life decisions: he made a list of pros and cons. Here is his note, probably written in July of 1838.

Darwin’s list. (Click for closer view)

Darwin’s list. (Click for closer view)

Centered across the top is written “This is the Question.” The left column is headed “Marry” and begins with “Children (If it please God). Constant companion (Friend in old age.)” And in the “Not Marry” column we read, “Freedom to go where one liked. Conversation of clever men at clubs. Not forced to visit relatives. Loss of time.”

You can almost see the the scores being added up in his head. Children worth 10 points. Freedom to go other places, lets say 7 points. Friend in old age, 5 points. Add up the scores and see what you should do.

—

But people aren’t the only ones making big decisions. Right now, deep inside your large intestine is a humble Escherichia coli cell, better known by his short name E. Coli. (He has some cousins that are dangerous to humans, which also go by the same name. But all humans have helpful E. Coli which help with digestion.) He’s hanging out there with several million others just like him, looking for a meal. Like his pals, he has several long tail-like structures called flagella that he can spin like a dog wagging its tail. To do so costs a lot of energy, and propels him tumbling forward randomly.

An E. Coli cell spinning himself forward into the unknown.

An E. Coli cell spinning himself forward into the unknown.

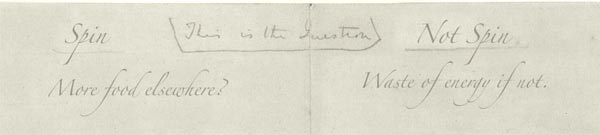

He doesn’t have eyes or ears; he only knows how long it’s been since his last meal. If he could find a pen and paper down there in your gut, he might make a list like Darwin.

E. Coli’s note. (Artist’s interpretation.)

It might seem like a small deal for you, but this is the only decision that our little E. Coli friend makes, and that makes it the most important decision of his life!

His list is like Darwin’s, with but with simple points. Having food recently is a point for staying still. Not having food is a point for leaving.

—

What do Darwin, E. Coli, and the online game addict all have in common? Yes, they are all making big decisions, in a way. But they also all posses a value system for helping them make those decisions.

The E. Coli values food. And if he isn’t getting any, it may be worth it to go tumbling into new territory. His value system is very simple, and a good scientist could deduce it by looking at the proteins and chemicals that the cell is made of. On the other hand, Darwin probably wouldn’t want anything from your large intestine. He valued food too (albeit different varieties), but he also valued children and companionship. He valued time, freedom, good conversation, and a million other things that you, as a fellow human, understand.

And the game addict writing that email valued my game. He valued it more than his paycheck.

The human value system is much more complex than that of E. Coli. Even the most boring soap opera plot require deep understanding of who wants what, and how they are pursuing those goals. Yet this complexity, the same complex value system working in your head right now, is not without patterns. These patterns are being researched by scientists with clever experiments and increasingly powerful brain scanning technology.

Talking about the value system can be hard—like trying to point at air. It is something so close to us and so obvious: of course Darwin wanted both companionship and time, of course sugar tastes better than rocks, of course you want to watch a funny movie more than a boring one. Yet the system that gives rise to these values holds huge power. And in this age of the internet and so much new media, this power is only growing. It is behind online games, behind Facebook, behind advertising, and so much more.

—

If you’ve talked to me in the past few months, you know that I’m considering writing a book around these ideas. I’ve collected a lot of fascinating nuggets this winter, and with a little perseverance I hope to write them up here before this blog rusts out from disuse.

By the time of Evernight, my company was beginning to shift away from massively multiplayer games in order to get into e-commerce. That was the cool thing in 1998. Sadly, this was just the time online games were beginning to take off and become the multi-billion dollar industry it is today. Shortly after the player’s email, I transferred off of Evernight for other reasons. I never heard from him again. Recently I heard secondhand that he’s doing fine—and actually didn’t like the job that much in the first place.

However, we do know firsthand what happened to Darwin. At the bottom of his note, on the “Marry” side, he came to the final summation of his values, writing “My God, it is intolerable to think of spending one’s whole life, like a neuter bee, working, working, & nothing after all. No, no won’t do. Imagine living all one’s day solitarily in smoky dirty London House. … Marry, Marry, Marry. Q.E.D.” He and Emma were married on 29 January 1839. They remained friends and companions into old age.

###

Related links:

- See Evernight as it looked in old days at the Internet Archive. It was later purchased by rabid fans and continues to run to this day.

- UltraCorps was later resold to Steve Jackson games, where it is playable today.

- The E. Coli example, and lots more about the importance of values, can be found in the wonderful book Your Brain is Almost Perfect, by Read Montague.

- Curious about video game addiction? Tom Bissell recounts how he was addicted to video games and cocaine.

- Charles Darwin and Emma Darwin at Wikipedia.